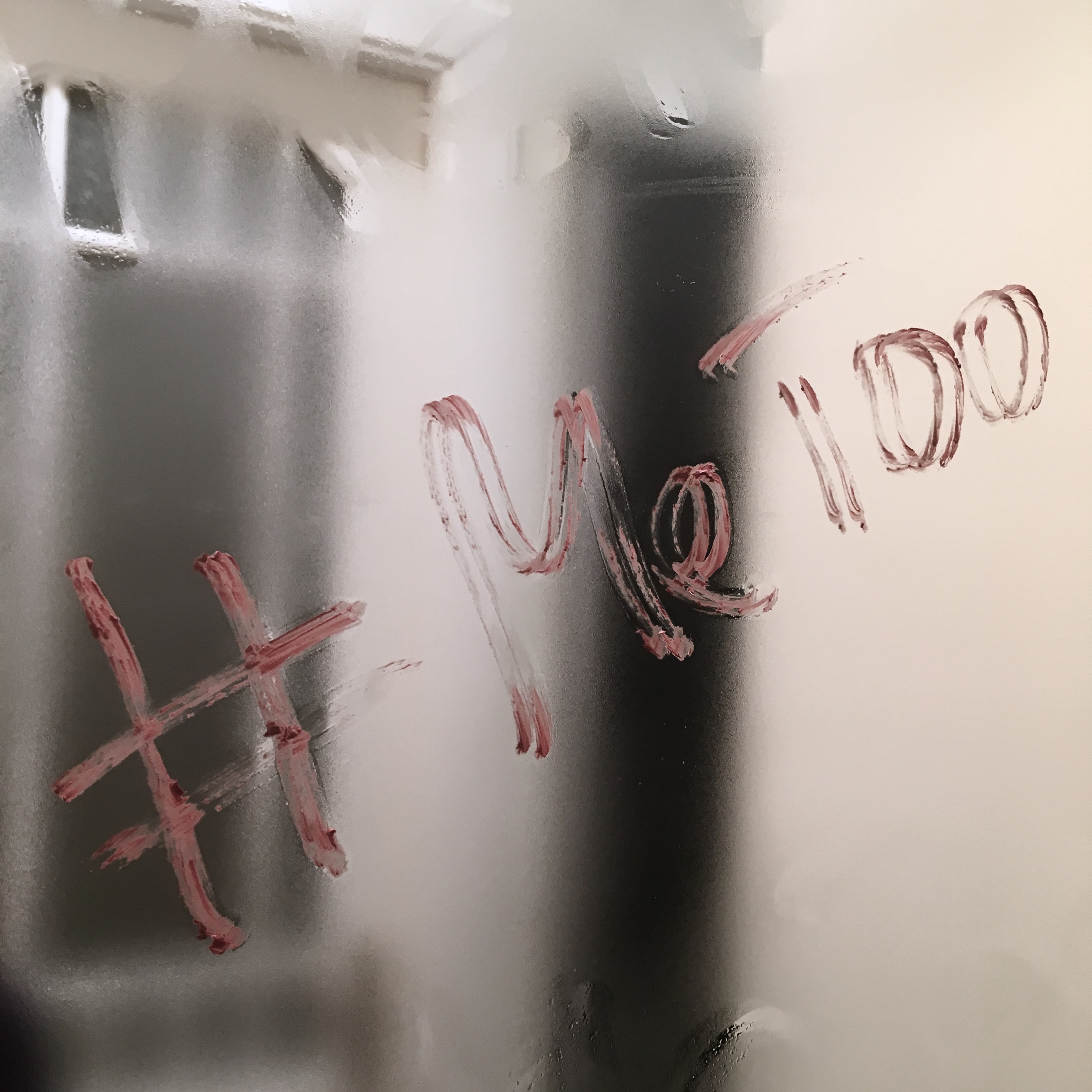

Right now, #MeToo is all over social (and other) media. The campaign – started in the wake of the recent revelations about Harvey Weinstein’s disgusting behaviours towards women – gained particular traction as (mostly) women started to post #MeToo as their status on social feeds, in order to indicate that they, too, had been sexually harassed or assaulted, so “we might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem” (as one typical comment to such a post reads).

Witnessing the pervasiveness of #MeToo status posts on my own social media feeds, I reacted, first with a short comment on a friend’s #MeToo status (see screenshot), then with a longer post on my own Facebook wall. Following my friends’ reactions to my post as well as other online discussions around #MeToo, this blog article is my attempt at structuring my thinking better than a string of random comments on social media can provide for.

One word of caution for those who read on: I write this as someone who has experienced sexual harassment and limited forms of sexual assault (for examples, see my Facebook post linked above). However, I consider non of my own experiences as traumatic, and I’ve been spared the more intrusive, disgusting, and violent forms of aggressive sexual assault – that, unfortunately, so many have explicitly described or implicitly hinted at in their own #MeToo posts. For those who believe that sharing experiences contributes to finding solutions, a good place to go is Musa Okwonga’s blog which he opened for (anonymous) contributions on #MeToo. With all this in mind, I’m aware of the fact that some of my thoughts in the following paragraphs might sound useless or even cynical to some who’ve gone through traumatising experiences. Should this occur, I apologise from the depth of my heart. If anything, my aim is to reduce suffering in all its forms – the painful memory of suffering, the fear of future suffering, the experience of actual suffering in the present, and the timeless suffering that cannot be linked to anything but itself.

Back to #MeToo: So – what’s all this about and what do we need to take away? Let’s start with three points that come through loud and clear in everything I read over the past couple of days:

- Sexual harassment and sexual assault are pervasive phenomena of our times. Maybe it has always been like that, maybe our day and age are worse. In either case: I haven’t heard of a single woman who said that she was never ever in her life sexually harassed or assaulted, and – to make clear that this is not only a gender issue – I’ve also heard of many men who have had similar experiences. There’s no point denying this pervasiveness.

- Sexual harassment and sexual assault create suffering for the one who’s being harassed or assaulted. Overstepping somebody else’s boundaries with regard to their sexuality (which often means: their body as the most tangible appearance of this sexuality) creates distress, pain, anger, and deep suffering – quite often for a very long time after the actual occurrence. This effect is at the very core of such transgressions, and it is what’s distinguishes them clearly from harmless flirtations, consensual body contact, and mutually agreed upon passionate sex (all of which, by the way, might come in kinky forms, but that’s a different matter).

- There’s a broad range of manifestations of sexual harassment and sexual assault. It can come in many different behaviours – from that unsolicited compliment on looks in a professional context and this obscene message received from a business partner all the way to physical violence, abuse, and rape. Also, the effect of such behaviours on the harassed or assaulted person can be very different – from mild annoyance all the way to outright trauma. And: It’s not like seemingly “smaller” behaviours always leave seemingly “smaller” traces, while seemingly “big” things cut seemingly “big” wounds. Some people deal with an unwanted one-night stand if it was just a bad choice of cocktails, and some people are triggered by a tiny raise of an eyebrow to go down a tunnel of fear, fight, or flight.

Putting these three points together, we end up observing that our times are plagued with a pervasive tendency of some members of our human species to inflict suffering on others – the exact form of which, however, is often hard to pinpoint, because the suffering produced is logged in the bodies, hearts, guts, minds, and memories of the ones being harassed or assaulted. This issue is exacerbated by the fact that the specific circumstances of sexual harassment or sexual assault are still enveloped in sheaths of shame, blame, and guilt on the side of those who are suffering – even in the very moment when they are happening. It’s easy and socially accepted to say: “Excuse me, you’re standing on my toe!” – usually resulting in the other person stepping off our toe and apologising. It’s everything but easy and socially accepted to say: “Excuse me, your physical closeness is making me cringe!” – and much less common to see such a remark resulting in the other person distancing themselves from us and apologising.

I’m taking the freedom to skip all biological and evolutionary takes on this subject, as well as all broad cultural perspectives on gender roles, machoism, or feminism. Instead, I want to suggest that one of the biggest issues underlying the pervasiveness of sexual harassment and sexual assault is our inability to communicate properly amongst human beings, in particular in cases where emotions are involved.

How so? Here are four requirements that would have to be fulfilled in order for us to stop sexual harassment and sexual assault in their very first beginnings – and, as you’ll see as you read on – all these are requirements that most of us are far from fulfilling in our day-to-day lives, let alone when emotions, desire, or sexual arousal come into play.

- Whenever someone is stepping over our physical boundaries of sexual autonomy, the first thing we’d have to be able to say is: “I don’t like what you’re saying or doing!”. Given the wide range of situations and behaviours that can – or cannot – be experienced as sexual harassment or assault, it’s futile to expect that there can be general rules applicable to every single instance. It’s up to us to be clear about what we like and what we dislike. Most of us, however, fail miserably already when it comes to telling a waiter in a restaurant that the meat isn’t quite as well done as he claimed, when it comes to revealing to our partner that we abhor their latest flea market booty, or when it comes to disclosing to our boss that their strategic plan for developing our business unit is flawed. How, then, can we expect to tell somebody who’s coming to close that we don’t like this particular kind of closeness? In order to limit sexual harassment and assault, we need to get a lot better at telling people we disagree with what they’re saying or doing. In saying so, I’m painfully aware of situations where saying: “NO!” loud and clear doesn’t help at all – and might even lead to increased violence and aggression. And still: I would say that there’s no way around saying: “NO!” as early as possible, as loud as possible, and as often as possible. I call this the obligation to say no.

- Now, turning the perspectives around, what if you’re the active and enthusiastic party to whatever is going on? In this case, the duties are reversed. Whenever we’re pushing ourselves into somebody else’s physical space (literally or figuratively), we need to have all our antennae tuned into seeing, taking in, and acting upon hesitations, doubts, critical comments, expressions of dislike, and outright rejection. A while ago, #NoMeansNo was another popular hashtag around sexual harassment and sexual assault – and, yes: NO MEANS NO. Again, most of us are not really good at taking no for an answer – regardless of whether it’s the delivery man’s: “No, we cannot deliver your parcel today!”, the old friend’s: “No, I cannot come to your party!”, the business partner’s: “No, we cannot do this project with you!”, or our longtime crush’s: “No, I really don’t want to deepen our relationship!”. And, indeed, there might be situations were getting past no is a viable option and actually leaves everybody better off in the end. My point here is: Whenever physicality or sexuality is involved, there’s no alternative to accepting that NO MEANS NO. I call this the obligation to listen.

- Then, again turning perspectives, what if I’m the one who failed to say no or the one who happened to find myself in the fangs of one of those other people who are blissfully ignoring the need to listen? What, in other words, if something disgusting happens to me in the realm of physicality and sexuality? Obviously, how I deal with any single one of such experiences will have a huge impact on how I deal with future instances of whatever happened in the lead to and unfolding of that specific situation. Here, we’re running into a big conundrum of psychological hangups – which, I believe, is one of the reasons so many experiences of sexual harassment and sexual assault are so traumatic for those who suffered through them. Usually, when something bad happens to us, we take either of two roads: One is to take responsibility, admitting and acknowledging that we made a mistake – as in: “Oh sh*t, I totally screwed up on my application – no wonder I got rejected”. The other is to blame circumstances or randomness – as in: “No wonder I got rejected – I know they draw participants via a lottery system”. In the case of sexual harassment and sexual assault, both approaches fail: Taking responsibility produces rushes of shame, guilt, and self-flagellation; blaming randomness produces gusts of fear of experiencing the same thing again and raw vulnerability. A classic psychologists’ approach to healing trauma associated with sexual harassment or sexual assault is therefore to enable the suffering person to see that the perpetrator did wrong – offloading the blame to the person who committed the transgression. Which, however, can lead a ruminating mind into the same dilemma as before: Why, then, did he do what he did? Was it his responsibility, and if so, what if others act as he did? Or was it a random affliction, so it can happen again with anyone? And so on, and so on, and so on. In order to stay sane in all this, we desperately need the ability to healthily balance our minds between responsibility and randomness – again, again, and all over again, whenever the spectres haunt us. I call this the obligation to reframe.

- Finally, some are expressing concern that all these concerns might lead to a crumbling, withering, and ultimately dying of all that is fresh, creative, and buoyant in our ways of feeling, expressing, and exchanging whims of desire. I wholeheartedly disagree. However, in order to keep desire alive in its sparkling, nurturing, and sky-dancing forms, we need the ability to express genuine appreciation for what others say, do, or embody. And again, already in our mundane lives, we struggle to compliment others well. “Ohhhh, you’re sooooo beautiful <3<3<3”, is not a skilful compliment, nor is: “I wouldn’t have expected a partner of a large global consultancy to be so pretty”. And, just to make clear that this is not only about external appearances: “You’re so clever!”, is also not a skilful compliment, nor is: “What a surprise to see a boy who draws such lovely flowers!”. Genuine appreciation needs to be expressed in specific words, describing specific instances relevant to the situation or relationship at hand – and this is hard, because it requires observation, conscious choice of words, and clarity of intention. I’m yet to meet the human being who dislikes a compliment like: “Your answer to the journalist’s nasty question saved my day, because after that there was no need for me to further explain anything about the critical situation in our New Zealand branch”, or – to take things into a different arena – the one who doesn’t feel good about hearing: “Those flowers and heart-shaped boxes you sent me were gorgeous – I love it when you give me things“. I call this the obligation to appreciate.

I’m painfully aware of these requirements being of a tall order. And still: If those who suffered can say no the next time a threat comes their way, and if they can reframe over and over again, until the trauma disappears into thin air; and if those who’re afraid they might unwittingly afflict suffering to others can remember to listen, and if they can practice to appreciate well – then, we might be able to talk. And talk we must. And then, hopefully (and maybe naively), the small share of those who deliberately engage in making others suffer will continue to be marginalised, shrivel and shrink into powerlessness.

#TalkWeMust

That makes sense yes. Shame, it seems, is a word too ambiguous to be used without qualification. People often say, as an expression of compassion “Oh shame”, in the sense of a loss/humiliation. But I see a difference. Rebuke a dog vocally and note the response. It feels ‘shame’, like being repelled and drawn to you at the same time. There’s a sense of anxiety about deviating from the ideal (the will of the owner) which the dog is still very much aware of. It has a moral vision. Now ‘humiliate’ it by bathing it, or feeding it banana mush for dinner, and it rather appears confused. It has lost the ideal and its relation to it, i.e. a sense of what is right and proper. It has an amoral vision. This humiliation is the unwholesome kind that leads to depression etc precisely because the moral vision is lost. You can imagine another example of how taking off our clothes could make us self-conscious, i.e. it could trigger a sense of shame, but it would not necessarily be humiliating.

A valid perception for a victim of a sexual assault would be humiliation. And it is essential to validate a victim’s perception of humiliation, just to the point that it is affirmed, but not magnified. An invalid perception would be shame – which is in fact what the perpetrator, one would hope, should feel. I believe this is what you mean by the obligation to reframe.

It seems the #metoo campaign is at once an attempt at re-sensitising a sense of shame in perpetrators of sexual abuse, and an attempt to compel victims to re-frame their experiences as humiliation. That would be conventionally correct. But as long as the perpetrators feel humiliated and the victims feel shamed there can be no resolution.

The problem is that in an amoral society, where the consequences of challenging the law are worse than social scorn, the necessity to avoid incriminating oneself is greater than the need to regain one’s moral worth. For this reason, a perpetrator would rather be humiliated (become the victim and justify the experience with righteousness indignation) than be shamed (where he/she must admit being wrong). The victim, it follows, would try to recover their power by incorrectly re-framing their humiliation as shame (since the only thing worse than being wrong is not having any voice/agency at all). This is the travesty of an amoral world which puts actions above principles. In a moral world, a world of values, there is no incentive to second guess our perceptions. We can judge whether we are acting with integrity according to our/others values, but it would not serve to simultaneously question the very perceptions needed to make those determinations. In an amoral world however, we cannot even trust what we see.

Thank you for your comment! To clarify what I meant: I see a distinct difference between me taking responsibility and feeling shame for something wrong that I *did* (e.g., stealing, hitting etc), and me taking responsibility and feeling shame for something that *was done to me*. In the first case, I very much agree with your argument. In such cases, taking responsibility and feeling shame is a (self-) corrective mechanism to prevent future misdeeds. In the second case – which is the case when a victim takes responsibility and feels shame for having been abused (as a psychological mechanism to deal with the randomness of being a victim and in the desperate attempt to make sense of a traumatic experience) – the guilt and self-flagellation gets in the way of the victim moving on from the experience. In these cases, it’s therefore an obstacle and not a (self-) corrective mechanism. Does this distinction make sense to you?

Great article. One point though: how does taking responsibility necessarily produce rushes of shame, guilt, and self-flagellation? And how is a sense of shame a failure? My father used to say “go to your room and think about what you did”. I took him literally. The isolation meant i could examine the situation alone without having to save face in company. So I thought about the situation and often found my actions wanting, but i also often found his responses heavy handed/out of touch with reality. So shame led to insight, and i am forever grateful that he cultivated that in me. Shame (Skt. hiri) is not the abysmal depression we so commonly fear. Remember the lojong slogan: “drive all blames into oneself.”

Hi, will you comment on my newest post, it’s a new blog? “You might want to think twice before you start groping sir”.. Thank you! Love your piece btw!